Day Books

On September 26th, some kind soul sent me a Facebook post stating that it was the birthday of Johnny Appleseed (1774-1845), the folklorish character, born John Chapman in Leominster, Worcester County, Massachusetts. This always reminds me of a “day book,” a journal of accounts kept by Mansfield, Ohio storekeepers Sherwood and Sturges from 1815 to 1817. My own ancestor, Andrew Richey, is located on page 100, under date May 18, 1816, debit of 6 ¼ cents for paper, 12 ½ cents for postage on his letter, and $1.50 payment on his account. The same day, who should wander in, but “John Chapman or as some say Appleseed”, debit on tobacco, $1.00. This is the only contemporary record where Chapman identifies himself as that character of folklore, brought to life to schoolchildren worldwide by writers such as Rosella Rice, Newell Dwight Hillis, and others. But did my ancestor meet him in the store that day? Probably not. They were 22 customers apart.

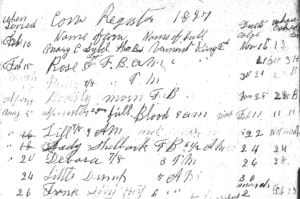

G.W. Miller Cow Register 1897

The ledger, referred to above, is located in the Ohio History Connection, our state archives, in MSS 539 – Sturges Family Papers, Box 1, Folder 15. It was microfilmed in 1984 and sponsored by our OGS volunteer coordinator (at the time), Mary Jane Henney, and, no doubt, is the reason that we have a complete photocopy here at the Samuel Isaly Library. This suggests that any rights might now be with the Ohio History Connection who hold the original manuscript. Perhaps I shouldn’t include an image of page 100 listing my ancestor Andrew Richey and the famous “John Chapman or as some say Appleseed” in this article without their permission. I chose not to give them a call and have included an image from another store ledger that we hold at OGS. The point is that manuscript copyright law is different than book copyright law. An unpublished work is protected for the life of the author plus 70 years – death date of Sturges or Sherwood plus 70 years – probably safe there! If it is a corporate author (is the store a company?), then it is protected for 120 years – 1817 plus 120 = 1937. It must be safe to use! But, wait just a second! The owner of the original manuscript can assess a fee for use of something they hold. The archives may have a fee for a paper or digital reproduction of the item and they may have an additional fee for one-time, non-exclusive use of an image or passage from the manuscript. Keep this in mind when ‘borrowing” images from manuscripts found online or in an archives.

How does a user find a ledger such as the Sherwood and Sturges Day Book? Our OGS online catalog is among the many choices in the “Visit the Library” section of our newly designed website – https://www.ogs.org/visit-the-library/ Search for the title or the two surnames “Sherwood Sturges” and the entry comes up with the call letters as well as an index to the work made by our library volunteer Maxine Kinton. Our entry also says that the original is at the Ohio Historical Society. Their online collections catalog is under the “Learn” tab at https://www.ohiohistory.org; however, the same search yields no results. The collection there is listed under “Sturges Family Papers” and the day book simply isn’t mentioned. However, a reference note refers to Ohio Memory – https://ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/aids/id/3080 – and here, one finds a 7-page finding aid to this specific set of manuscripts. The description for Folder 15 does note the day book created by Eben Perry Sturges and Edward Sturges, Sr. – remember that ours is labeled “Sherwood and Sturges”? The next folder (#16) includes receipts from the E.P. and E. Sturges business and there lies the answer. It had formerly been the firm of Sturges and Sherwood. The OGS index is not mentioned. Locating a manuscript can sometimes take a lot of work, but it is quite a treasure if an ancestral name is discovered.

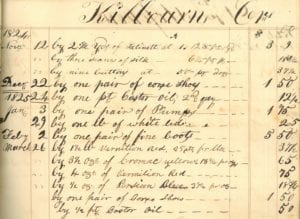

Lucius C. Strong Account Book 1824

A day book is defined as a journal in which transactions have been entered. These are often account records but day-to-day diaries are also often categorized under this term. There are sometimes credit entries (CR) and debit entries (DR). Many researchers incorrectly believe that their relative is a physician when they see that “Dr” with their ancestor’s name. The monetary amount is generally provided as well as the item(s) purchased if it is a store account like that of Sherwood and Sturges. Some day books are chronological, listing each purchaser as they come into the store. Many account books are arranged by the buyer. All debits and credits for your ancestor are noted on the same page. The pages for each family’s account are generally not alphabetical. Each new customer was added on the next empty page. Many have an index to customers at the front. Regulars to the establishment may have multiple pages under their name in the book. Remember that our ancestors lived in an agricultural-based economy. Farmers kept day books identifying the crops planted, produce sold, and those who came over with their livestock to pay a visit to the prize bull or stud horse. It is not usual to find family accounts, even lists of births and deaths of the children, squeezed in between the account pages if the manuscript is a farm journal.

How does one locate day books in a library catalog? Does “daybook” vs “day book” vs “day-book” make a difference in a computer database search? You bet! Users may also be aware that libraries use a pre-coordinated system in cataloging. With Library of Congress subject headings, there is no entry for “day books”. That might be a problem! The term “journals” was my next thought. For Journals (Accounting), the preferred cataloging term is “Account books”. For Journals (Diaries), the Library of Congress recommendation is “Diaries” in the cataloging entry. Did we make the search process more expansive for you? I won’t go into some of the other subject-assigning systems used by libraries and archives.

Looking through the manuscript collection catalog at OGS, I see many items that could fit under the term “day book”. I didn’t pull each to see if it actually fits in our story but just examine this list and the terminology used and the many possible synonyms. They all may be valuable for a catalog search.

010 – Arter Store Ledger, Columbiana County, Ohio

31-5 – Journal of the Cleveland, Lorain & Wheeling Railroad Company, Lester, Ohio

61-2 – John Cantlebery Day Book

84-5 – Rolla Smith Account Book

126-4 – Stephen Balliet Account Book

126-5 – James P. Reed Day Book

157-1 – Robert Gordon Account Book, Beaver Falls PA and Warren OH

158-3 – William Johns Store Ledger, Noble Twp., Auglaize Co OH, 1848-1851

158-4 – Eden B. Reeder Account Book, Grand Junction Railroad, 1859

188 – Account Book 1852-1854 for Benjamin Jenney, Greenwich Twp., Huron Co OH

220-8 – Jacob Baugh Account Book

220-9 – George W. States Ledger

303-3 – G.W. Miller Cow Register 1890-1902, Orange Twp., Ashland Co OH

356-2 – Adam Innes Blacksmith Account Book, Ruggles, Ashland Co OH

356-5 – Samuel Mitchel Day Book 1850s

375-7 – Lucius C. Strong Account Book 1824-1856, Worthington OH

375-8 – H.T. Strong Farm Account Book, Constantia, Delaware Co OH, 1863-1896

384-10 – James Silver Day Book, 1827-1831

413-1 – C.C.&C. Railroad, Westerville, Ticket Sales, 1870

Why could a day book be important to us in our research process? They are generally unique. They are made up almost entirely of names. They are tied to a community and identify those friends, associates, and neighbors in the FAN Club principle developed by genealogist Elizabeth Shown Mills. The store accounts are usually dated and are proof of residence if you are applying to a First Families group. They don’t give an exact residence but the family certainly lived within a horse’s ride of the business. I recommend that you search for these day books in the geographical region where your ancestor lived. Look for them in manuscript collections at libraries, universities, museums and in genealogical society holdings. They can be an exciting find.

Tom Neel, OGS Library Director